From novice to expert: what teacher development frameworks can teach us

Teacher development and cleaning products — the way my mind works!

Teaching a language, especially when you’re a novice, can be really daunting. In fact, the word “daunting” immediately brings to mind a Duck commercial that was constantly on when I studied in Australia. The voice-over would go, “Cleaning your bathroom can seem like a daunting task”, and the small bathroom would grow huge with the woman (why is it always a woman, by the way?) tripping over herself. That nerve-racking image of an evergrowing room to clean – and sometimes the opposite image, of walls closing in on me – is perfect to describe my mental state in my first years as a teacher.

I’m an anxious person by both nature and nurture, only apparently calm on the surface (much like a duck!), so the first impact of a new profession would probably have made me suffer regardless of what support I had or didn’t have, especially considering how much of a responsibility teaching is. However, there is something that I believe would have helped soothe me when I started: the language teaching frameworks we have available nowadays, courtesy of Cambridge Assessment, the British Council and EAQUALS.

Much like the CEFR defines language proficiency levels with can-do statements, these frameworks describe what teachers can do at different stages of their career. And that’s lesson number one of what I could have learned from the frameworks:

- Teaching has developmental stages, too.

Color me naive, but that was a realization I wasn’t able to make on my own when I started: that teachers – just like our students – are also allowed to have stages of development. I didn’t have to be ready for any and everything just because I had graduated from college or because I had been hired as a teacher by a good language school. I was a novice. It was expected that I behaved as such and got the wrong end of the stick here and there – which, evidently, I did (and boy, did I ever!).

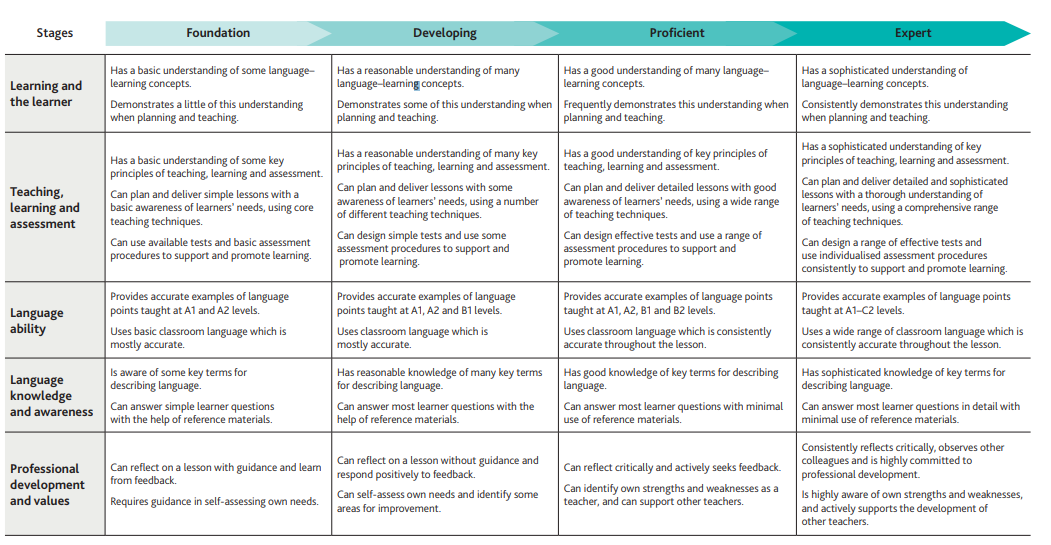

Summary of the Cambridge English Teaching Framework available at https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/teaching-english/professional-development/cambridge-english-teaching-framework/

- Don’t underestimate your abilities. You should build on and develop from what you CAN do.

There’s a lot that a young professional struggles to do. For one, lesson planning was to me like Duck’s bathroom: a teaching hour would take me 2 or 3 planning hours (on a good day!). However, focusing on what I couldn’t do yet gave me the wrong impression that I was utterly incompetent. More importantly, it drew my attention away from my students – not to mention the toll it took on my health. As Donald Freeman mentioned in his talk at IATEFL 2019, that’s a disservice that many teacher training initiatives do: they focus on what teachers can’t do instead of helping them realize and grow from what they can do. As a backfiring result, developing as a teacher can seem like an unreachable target that some teachers end up giving up on.

- We’ll have jagged profiles and that’s fine, provided we move on.

It’s unusual for people to be at a single stage for every criterion. If you analyze the frameworks, especially the detailed descriptors, you’ll see there are categories that don’t necessarily go together. You may be a great lesson planner but still struggle with classroom management. Also, you may speak and write beautifully, but not be able to explain/exemplify language to students (or maybe you can explain language reasonably well at a B1/B2 level, but be at a loss with the extremes of A1 and C2). Finally, you may have mastered all that, but still be learning the ropes in terms of how to incorporate technology to your teaching, how to assess students, or how to integrate students with disabilities.

And that’s OK. We can’t be expected to know and be able to do everything. What we should be expected to do – and will fail to if we don’t admit our current stage of development – is to look for help and development where needed. To this day I beat myself up because of the way I treated a student with an unclearly diagnosed disability – but did I look for assistance to understand the student and learn how to help him learn English? Not much. I (mis)understood from a quick conversation with my boss and the student’s mother that I should already know how to teach him, and off I went – to botch it all up, obviously, only to then learn my language school offered a hotline to assist teachers that had students with disabilities.

4. Don’t overestimate your abilities, either. There’s always something for us to improve.

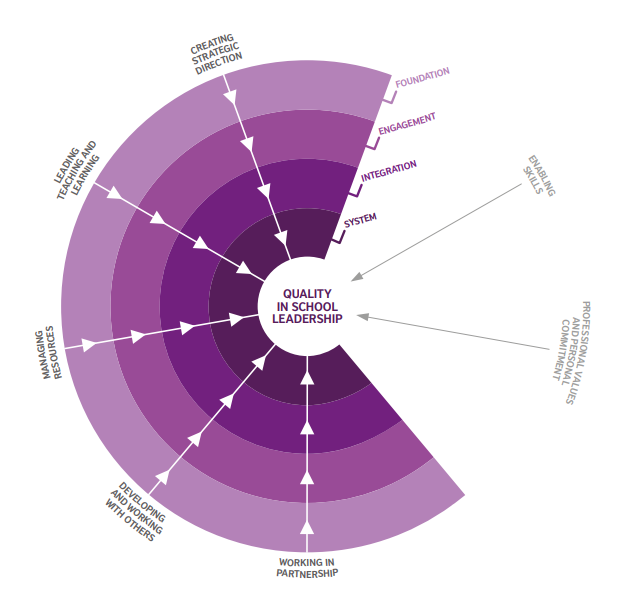

When we look at the frameworks and their accompanying competence statements, we can see how many areas language teaching involves. And then there are more frameworks – the British Council has also developed one for school leaders and one for teacher educators (because of course being a great teacher doesn’t make you an instantly decent coordinator or teacher trainer).

British Council’s CPD Framework for School Leaders

Even if we master most of the teaching skills for our context, we may still have a lot to learn if we change jobs. As the frameworks show, knowledge about the learners and the language they need is an essential component of what we do – and teaching very young learners is quite different from teaching adults, teaching General English can be miles away from teaching English for Specific Purposes, and so on, so forth. In fact, it’s funny how we demand from ourselves (or bosses expect us) to be able to teach any age range, proficiency level, context and type of English competently more than we expect from the way-better-paid dentists (just ask an orthodontist to extract your wisdom teeth and see how it goes) or lawyers (please don’t even try to settle a family dispute with a criminal lawyer – that will likely go awry).

Incidentally, much like I’d be suspicious of dentists and lawyers who claim to be able to do everything in their humongous fields, I’ll just come out and say I don’t believe teachers who say they are ready to teach everything and everyone — what I jokingly refer to as teachers who find themselves “too sexy“. We may well be ready to *learn* how to teach everything and everyone, but that’s a work in progress, not a finished product. Whenever we take on a new challenge, a lot of preparation and effort is required, as well as, hopefully, the support and feedback of our peers, managers and mentors.

- Expert teachers were once novices, too.

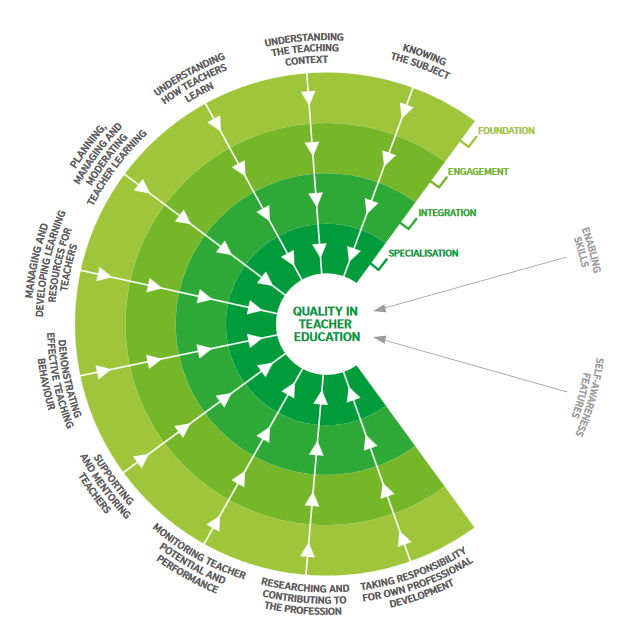

British Council’s Teacher Educator Framework availale at https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/Teacher%20Educator%20Framework%20FINAL%20WEBv1.pdf

You know those teachers whose work we admire – maybe an experienced colleague, a famous materials writer, our first teacher trainer, or that person we saw deliver enlightening sessions in conferences? When we see them perform seemingly effortlessly what is still difficult for us or when they come up with great simple answers to questions we’ve had for some time, we may at times feel discouraged and disheartened, as if we belonged to another caste of professionals. If we keep those people in mind when we read the frameworks, we may recognize them in the descriptors of the highest levels there. However, that certainly doesn’t mean they started off at that stage. For the most part, there was a long path of hard work we never got to witness. And the descriptors before that clue us in: they bring our current stage of development, so we can check the suggestions on how to get from our point to the next and from there to theirs, maybe with baby steps (so we don’t run before we can walk), but in that direction that we’ve chosen.

P.S. (Hat tip: Ricardo Barros): It should go without saying that developing our own teaching or teacher training skills and abilities doesn’t mean we’ll all have the success of a Vinicius Nobre or an Isabela Villas-Boas. Not everyone will have his charisma and range of facial expressions or her elegance and multitasking skills, or even the je-ne-sais-quoi that brought them to positions they have today. Still, there’s a way we can build our own path with our own style, our own luizotavioness as Luiz Otávio Barros explained in his plenary in the 16th BRAZ-TESOL International Conference in Caxias. And more importantly, there’s a way we can all make sure we’re helping our students or teacher trainees to the best of our abilities.

- A positive and active attitude towards our own development is part and parcel of what it means to be a professional.

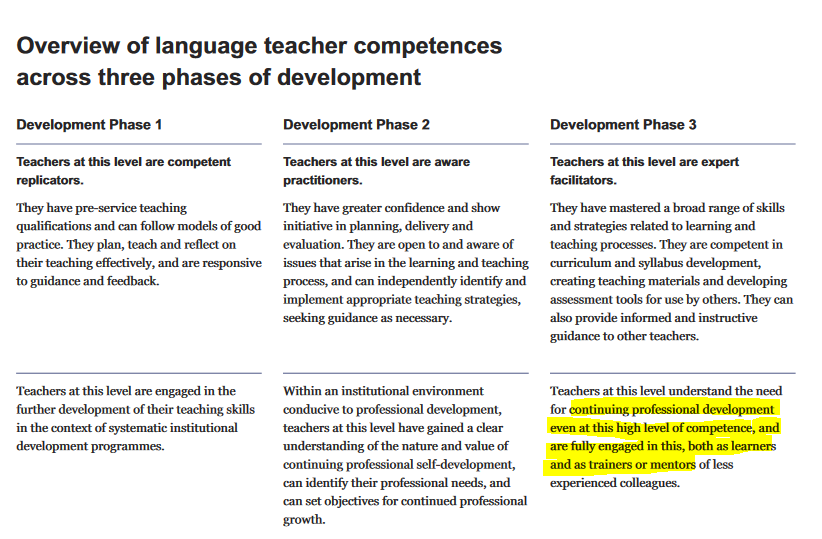

Eaqual’s CPD framework overview available at https://www.eaquals.org/wp-content/uploads/Eaquals-Framework-Online-070216.pdf

It’s all there: all three frameworks have a section of attitudes towards professional development. In other words, if we believe developing is not worth it, if we think our development is done and over with (too sexy, yeah!), or if we refuse to support other teachers who haven’t come as far in their teaching skills yet, – alas! – we’re back to square one.

In other words, as my disastrous interaction with the student with a disability taught me very early on, we owe it to our students to identify our developmental stage and to look for ways to grow from there, so – as again Luiz Otávio Barros keeps reminding us – we can help our students better. And I say we also owe it to ourselves: because when I couldn’t teach that student and probably made him feel bad about language learning, I wasn’t reprimanded by my employers – or perhaps I was, but that didn’t stick. What’s hurt me is that I failed my student big time (not in terms of giving him a bad grade, but rather the worst kind of failing: actually being unable to help a student), a feeling we teachers don’t want to have. What keeps us going, I strongly believe, is the kick we get from the joy learners show when they finally see themselves performing that task we taught them. That unique feeling, to me, is what turns ‘daunting’ into ‘well worth it’.